From the atmosphere to the ground: How biomass provides energy and removes carbon

Biomass supplies stable, continuous and low carbon intensity renewable electricity or bio-power as compared to solar and wind power, both of which are weather dependent with intermittent supplies. Another advantage of biomass over solar and wind power is its flexibility to be processed to produce bio-fuel in the form of bio-ethanol. The bio-fuel decarbonizes the transportation sector using existing supply chains and infrastructure, as opposed to electrification of transportation via solar and wind power, which requires investments into charging and battery energy storage systems.

In addition, biomass absorbs carbon as part of its natural growth, reducing the carbon emissions due to biomass related use for bio-power or bio-ethanol. Figure 1 shows that when bioenergy processes are integrated with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), the resulting carbon emissions could be ‘net negative’, with the carbon dioxide stored in suitable underground geological formations permanently. Furthermore, existing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere or carbon dioxide that was historically emitted can be removed using biomass for carbon removal and storage (BiCRS), resulting in net negative carbon emissions as well.

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)

Bio-power from biomass

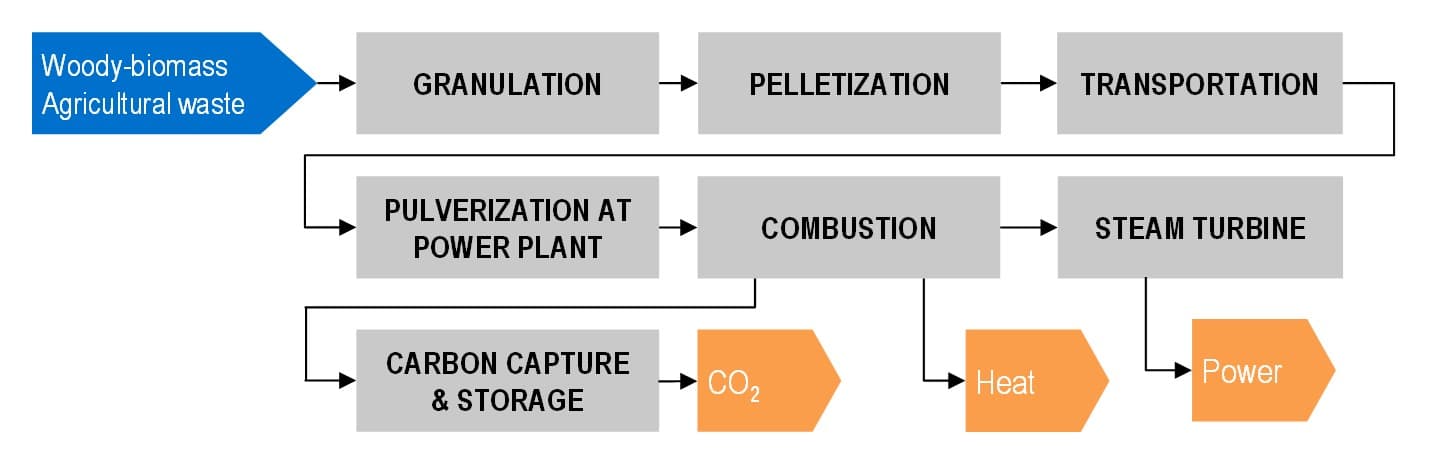

Bioenergy from bio-power can be generated via direct combustion of biomass to provide heat for steam Rankine cycles. With woody-biomass containing low amounts of ash and a sufficient calorific value, it is currently the most used biomass for the production of bio-power. The simplified process flow in Figure 2 shows the simplified process for the generation of bio-power from woody biomass. Woody-biomass in the form of off-cuts, barks or products from the forestry industry are first granularized before it is compressed and pelletized into wood pellets. The wood pellets are transported to the thermal power plant, where the wood pellets are pulverized (ideally to less than 75 μm in size) for injection into a furnace via pressurized air flow. The biomass particulates are ignited in the furnace to provide heat, converting water to superheated steam for a Rankine cycle to generate bio-power. The flue gas from the combustion process is sent to a carbon capture and storage system for post-combustion carbon capture using an amine-based absorption system.

Figure 2 - Simplified Diagram for Bio-power from Biomass Combustion with Carbon Capture and Storage

The technology developments in bio-power from biomass focus on the improvements to grinding or pulverization of biomass aimed at reducing the particulate sizes. A smaller particulate size reduces the ignition delay of biomass in the furnace and reduces the need for modifications to the burners’ configuration.

There are also developments to improve the properties of biomass other than woody-biomass to generate bio-power. Other types of biomass include agricultural waste, plantation wastes and organic fractions of municipal solid waste which may require pre-treatment to improve its inherent properties before direct combustion in thermal power plants. During the combustion process, inherent properties such as chlorine are devolatilized to form chloride compounds which are corrosive to downstream equipment and pipelines. The alkali metals in the agricultural waste also devolatilize, forming lumps or layers of slag consisting of aluminosilicates that have melting temperatures of 700˚C (conventionally it is above 1000˚C), decreasing heat transfer efficiencies to the water tubes inside the furnace. If the agglomerated material or slags are too excessive, the furnace needs to be shut down for maintenance, disrupting operations of the power plant and the supply of electricity.

Bio-power from biogas

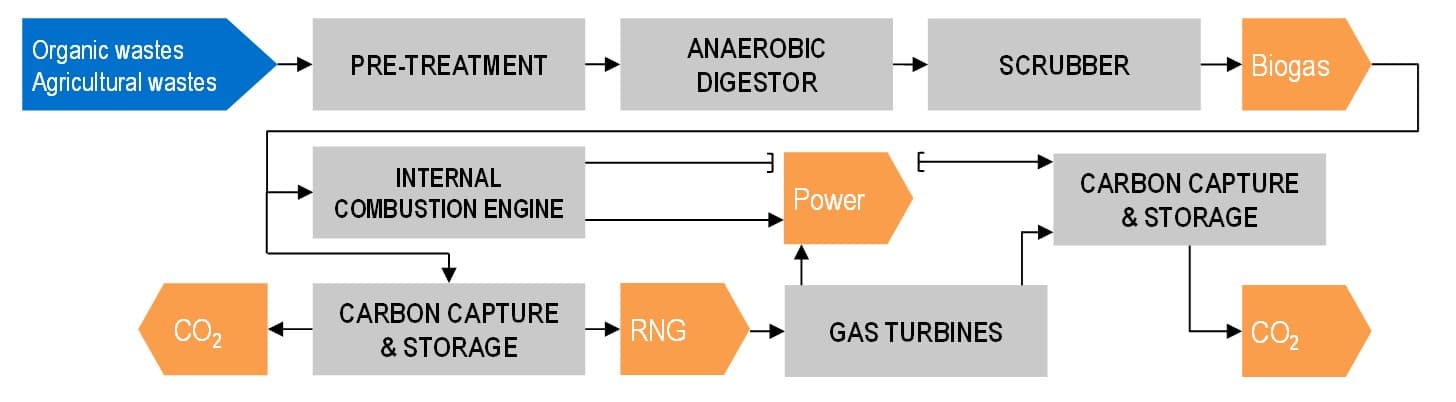

Bio-power can also be generated from the combustion of biogas in internal combustion engines. Biogas is generated from anaerobic digestors that consume agricultural waste and organic fractions in municipal solid waste (Figure 3). Anaerobic digestors are loaded with microorganisms (an inoculum) at a certain composition to decompose the renewable feedstocks (at 35 to 55˚C, ambient pressure, pH of 5 to 7) and produce a gaseous mixture that contains biogas, hydrogen sulfide and moisture. The gaseous mixture is treated with a scrubber to reduce the hydrogen sulfide and moisture content, producing biogas that contains 50 to 70 percent by volume of methane, with the rest consisting of carbon dioxide. The biogas can then be used for generating heat or power directly in an internal combustion engine or can be processed further by separating and capturing the carbon dioxide, producing a methane rich stream that is essentially renewable natural gas (RNG). The renewable natural gas can be used further for power generation via gas turbines or combusted directly for heat production. Bio-power from biogas or RNG is an established technology, with developments aimed at optimizing the operation of biogas engines. Examples of optimization measures include the reduction of biogas engine’s start-up time and the reduction of nitrogen oxide emissions.

Figure 3 - Simplified Diagram for Bio-Power from Biogas/RNG Combustion with Carbon Capture and Storage

Bio-ethanol from biomass

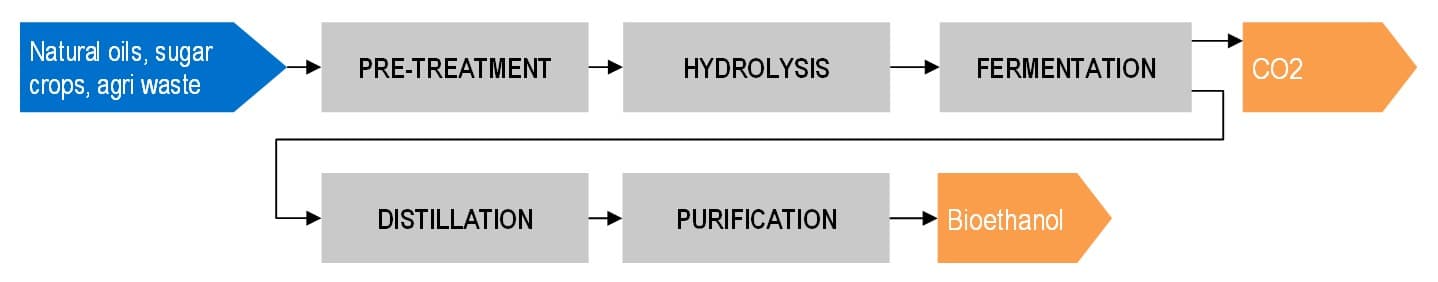

The process of bio-ethanol production is dependent on the type of feedstocks, with commercial processes using biomass crops such as corn and sugarcane generally following the stages shown in Figure 4. Natural oil, sugar crops or agricultural waste undergo pre-treatment processes, followed by (but not limited to) enzymatic or acidic hydrolysis (150 to 200˚C, up to 20 bar) to produce sugars. The sugars are then fermented (30 to 35˚C at ambient pressures) to produce an output stream that undergoes distillation to separate the impurities and is then purified to achieve the desired concentration of bio-ethanol. The fermentation process produces carbon dioxide with concentrations that are above 99 percent by weight and can be sent for storage or sequestration at suitable underground geological sites.

Figure 4 - Simplified Diagram for Bio-ethanol production with Carbon Storage

Carbon Capture and Storage

When integrated with carbon capture and storage (CCS) system, the combustion of biomass in the form of solid or gaseous fuel (biogas or renewable natural gas) to produce bio-power has the potential to reduce its net carbon emissions to negative levels. Figure 5 shows a generic CCS process to capture carbon dioxide from flue gas. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the flue gas can be up to approximately 15 percent by volume, depending on combustion conditions. The carbon dioxide is captured using absorption and desorption unit with amine-based solvents. The most commercially used amine-based solvent is monoethanolamine (MEA), with carbon dioxide capture rates of 85 to 95 percent. The flue gas enters the absorber, flows upward and counter-current to the lean amine solvent that flows downward. The term lean refers to the solvent stream introduced at the top of the column, which contains negligible concentrations of carbon dioxide in the solvent. Carbon dioxide is removed from the flue gas in the packed-bed absorber column through direct contact with amine (40 to 65˚C). The carbon dioxide-depleted flue gas is exhausted into the atmosphere. The carbon dioxide-rich solution (cold rich solvent) is heated in a heat exchanger (with hot lean solvent) and sent to the desorption unit (100 to 120˚C, 1 to 2 bar) with a reboiler at the bottom and a condenser at the top. The reboiler produces a vapor stream that acts as the stripping fluid in the desorption column. Low-pressure steam used in the reboiler provides the thermal energy to release the carbon dioxide (at purities of 99 percent by volume) from the carbon dioxide-rich solution (hot rich solvent). The carbon dioxide vapor is cooled at the overhead condenser and is compressed in preparation for injection into the underground geological formation.

Figure 5 - Generic Carbon Capture Process

Technology developments for carbon capture and storage are focused on reducing solvent degradation and energy consumption of conventional monoethanolamine-based processes. The developments include new amine-based solvents that have less degradation, consume less energy and has a higher carbon capture rate compared to monoethanolamine. In some developments, non-amine solvents such as potassium carbonate that apparently do not degrade are planned for carbon capture at pressurized conditions.

Biomass Carbon Removal and Storage (BiCRS)

Biomass carbon removal and storage (BiCRS) is a bio or nature-based solution to remove carbon dioxide that is already in the atmosphere, with biomass crops absorbing carbon dioxide for various biochemical reactions for growth and utilizing soil as the carbon reservoir in the terrestrial biosphere. As opposed to anthropogenic solutions to remove carbon dioxide such as direct air capture followed by sequestration, BiCRS has lower infrastructure needs for implementation. With BiCRS, the biomass crop itself is the carbon absorption agent and stores carbon in its above ground plant matter (i.e. as above ground carbon), the roots and soil (i.e. as below ground carbon). Below ground carbon sequestration is the capability of each biomass crop to enhance the soil organic carbon levels by capturing atmospheric carbon and depositing it into the soil. The sequestration mechanisms involve the release of organic materials from the roots into the soil, a process known as rhizodeposition. Rhizodeposition produces oxalates (C2O42-) that are consumed by microorganisms, subsequently producing carbonates that are bounded to minerals in the soil such as calcium to form calcium carbonate.

The exact sequestration mechanism of above and (especially) below ground carbon is much more complex and is dependent on the type of biomass crop, climate related biochemical reactions in the soil by microorganisms and human activities. There is also a potential of carbon re-release due to agricultural practices, driving the development of alternative options for carbon removal and storage via biomass in the form of agricultural wastes, forestry wastes and plantation wastes. These wastes are buried underground to store carbon and mitigate re-release of carbon dioxide. There are also developments into thermochemical processing of biomass and to store its derivatives underground permanently.

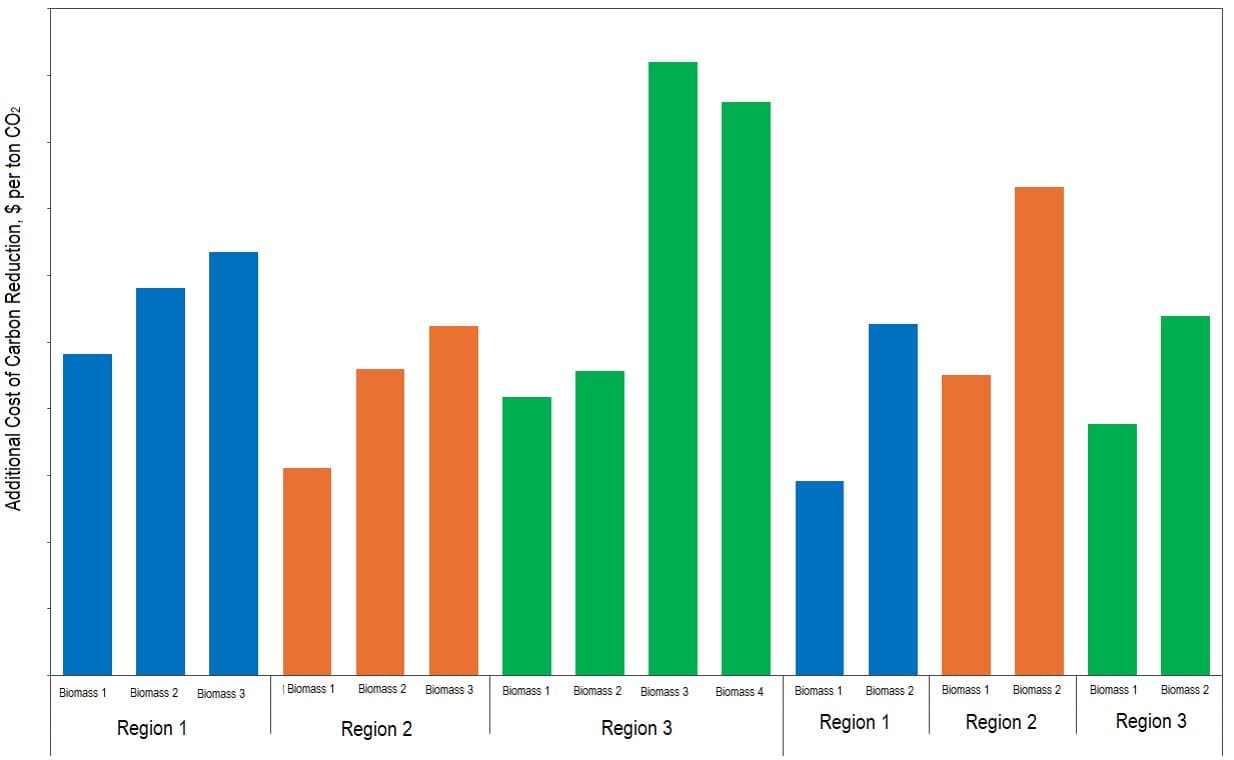

Cost of Carbon Abatement with BECCS and BiCRS

There are uncertainties regarding the amount of carbon that is reduced or removed by biomass, with some methodologies suggesting that the carbon emissions from the direct or indirect utilization of biomass could be underestimated. Yet, there are also evidences that previous methodologies do not fully account for the carbon abatement because of biomass use, mainly due to an underestimation of below ground carbon storage. These uncertainties impact the accuracy of the carbon reduced with the BECCS and BiCRS approaches, with the resulting cost of carbon abatement uncertain as well.

In the TECH and Biorenewable Insights reports, NexantECA provides a simplified assessment of the cost for carbon abatement via BECCS and BiCRS with selected types of biomasses using an in-house, proprietary seed-to-plant gate cost of production models (Figure 6). The cost of production models includes various stages of cultivation and utilization of biomass, including during the carbon absorbed during its growth, harvesting, transportation and processing stages.

Figure 6 - Cost of Carbon Abatement for Different Biomass in Different Regions

Find out more…

The report provides an overview of the cost of carbon abatement related to biomass energy with carbon capture and sequestration (BECCS) and biomass carbon removal and storage (BiCRS) for different types of biomass. The report lists the major and notable industrial players for BECCS and BiCRS. Technology developments in BECCS, recent advances in CCS technologies and BiCRS are also discussed.

Technoeconomics – Energy and Chemicals: Processing Challenges of Renewable Feedstocks 2024 program

This report provides a technoeconomic analyses of the pre-treatment technologies needed for the use of renewable feedstocks to decarbonize different processes. This includes the pre-treatment required for the direct combustion of alternative biomass for heat or power generation. The pre-treatment for other types of renewable feedstocks for biofuel and chemical production are also discussed.

Subscription and Reports: Technology and Costs Program

NexantECA’s Technology and Costs Programs examine the impact of new, emerging and improved industrial technologies on the comparative economics of different process routes in various geographic regions, as well as the cost competitiveness of individual production plants. These include:

Technoeconomics – Energy & Chemicals (TECH)

Biorenewable Insights

Cost Curves

Sector Technology Analysis

List of reports are available at: View all Technology and Costs Reports

The Author...

Mooktzeng Lim, Consultant

About Us - NexantECA, the Energy and Chemicals Advisory company is the leading advisor to the energy, refining, and chemical industries. Our clientele ranges from major oil and chemical companies, governments, investors, and financial institutions to regulators, development agencies, and law firms. Using a combination of business and technical expertise, with deep and broad understanding of markets, technologies, and economics, NexantECA provides solutions that our clients have relied upon for over 50 years.

For All Enquiries Contact Us